India 08.10.2015 Updated: David Abram

David Abram, author of the Rough Guide to Kerala, shares his favourite corners of India’s tropical southwest.

The Backwaters

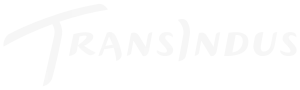

Houseboat cruises on traditional kettu vallam rice barges have become the signature experience of Kerala’s Kuttinad backwater region, and with good reason. But any traveller wishing for more than the most superficial skim over the glossy green surface of this fascinating part of the world will want to spend time there on dry land too, in order to gain a more authentic experience of the area and learn more about its unique way of life.

One option is to linger a few nights in a heritage homestay, such as Olavipe, midway between Kochi and Alappuzha. An old-favourite of this company, the 19th-century, Syrian-Christian mansion was one of the first ancestral homes to be opened to paying guests in Kerala, and still offers a wonderful time-warp experience. I love its four guest rooms, with their polished red-oxide floors, four posters and spilt-cane blinds, and the deep verandah on the cool side of the building, which opens on to a sandy courtyard.

Visitors are encouraged to explore the farm, where a cornucopia of exotic crops are grown organically, from areca nut and ginger, to pepper, vanilla, cinnamon and hibiscus flowers. The family’s boatmen can also take you out for trips on the adjacent Kaithappuzha backwaters where locals fish for karimeen (‘pearlspot’) in dugout canoes.

Owners Antony and Rema are perfect hosts and great ambassadors for their idyllic estate, where life appears to have altered little in decades.

TransIndus’ ever entrepreneurial team in Kochi recently came up with another great way to experience the backwaters. Half an hour out of the big city, an islet they’ve found on the fringes of Vembanad Lake hosts a handful of little farmsteads which you can travel to by boat, and spend the day exploring with the help of a guide, watching local people process coir, copra and other coconut-based produce and fishing on the surrounding lagoons. A sumptuous lunch of traditional Kuttinadi cuisine is a real highlights of this trip, which can be done in a day from Fort Cochin, or en route to destinations further afield.

The Hills

An enduring source of frustration for hill lovers like myself has been the reluctance of the Keralan Forest Service and big tea and coffee estates such as Tata to allow people on to the tops of south India’s highest mountain range. It’s understandable: if the gates to this precious, unspoilt area were thrown open one can but imagine the destruction that would be wrought by hordes of daytrippers. However, a couple of gaps in the protective cordon thrown around the high ranges do exist, if you know where to look.

One is Kolukkumalai, a tea plantation outside Munnar, on the Tamil side of the state border. Among the highest tea estates in the world, it was the last to be created in India by the British and retains its original factory and machinery, which produces a superbly fragrant, organic leaf tea in time-honoured fashion.

Our team in Kerala recently acquired the lease on a row of pluckers’ lines (pickers’ cottages) at Kolukkumalai and converted them into a delightful 3-roomed lodge, complete with avocado-coloured walls, comfy beds with proper duvets and a wonderfully breezy verandah boasting expansive views.

It’s the perfect spot from which to gaze at the sun rising over the Palani Hills, to the northeast. Temperature inversion is common in the early morning, ensuring ethereal vistas for earlybirds.

The lodge lies a very bumpy hour’s Jeep ride up a dirt track from road level. When you get there, you can lounge in the garden enjoying the blissfully cool air, visit the tea factory and stroll through the surrounding bushes to watch the pluckers at work. Those with the lungs for it can also strike uphill, beyond the tea line, to the grassy slopes of Meesapulimalai, south India’s second-highest peak, which can be scaled in a couple of strenuous hours from Kolukkumalai.

Our team can also arrange longer, multi-stage treks, with night halts at camps miles from the nearest road, where you may savour the atmosphere of India’s last surviving patches of wildlife-rich shola forest. During my two-day trek, I saw wild elephant, langurs and a rare Nilgiri marten, who tip-toed into camp one evening after supper to pilfer food. And the sunset views down the valley into Tamil Nadu are sublime.

Festivals

For me, Kerala’s temple festivals – or utsavam - are reason enough to visit the south of India. Involving ranks of splendidly caparisoned elephants, ear-splitting drum orchestras and crowds of awe-struck onlookers, these intensely traditional events mostly take place in the cooler winter months, yet are visited by surprisingly few foreigners.

One of my favourites utsavam, is the 10-day Vrischikotsavam, staged annually in November at the Shri Poornathrayeesa temple in Tripunithura, on the outskirts of Kochi. The reason I love it so much is because it hosts an impressive phalanx of 15 elephants – quite a spectacle when they’re all lined up together, with three Brahmin boys standing on their backs waving yak-tail whisks, peacock feather fans and silk-and-gold umbrellas.

The elephants slowly process around the central shrine, the largest one carrying the deity on his shoulders. At each of the four cardinal points, the line pauses and the orchestra arrayed before the animals cranks out a gradually intensifying cycle of rhythms, watched by a melee of enthusiasts who punch the air in time with the complex drum patterns. Many of these fans are in the grips of a peculiarly Keralan form of insanity known as ‘ana pranth’, literally ‘elephant madness’. Some are so obsessed with individual animals they follow them around to different festivals, put pictures of them on their walls at home and create websites dedicated to them!

The other great thing about Vrischikotsavam is that it includes a full programme of Kathakali in the evenings, allowing you to experience this uniquely Keralan ritual art form in its authentic context (as against the sanitized, shortened versions you see in tourist theatres and hotels). A couple of times I’ve managed to stay up all night (albeit with a spell dozing midway through) to witness the dramatic disembowelling of the demon just before dawn.

Emerging from the temple with the crowd in their crumpled lunghis and sarees, to sip hot, sweet tea in the cool air of dawn as the sun rises above the palm canopy, is always a magical experience.

My Favourite Beach

One question I’m frequently asked by would-be visitors to Kerala is which beach I like the most. “The empty one” is my usual reply, and there are no shortage of those, especially if you’re prepared to travel north.

Kannur, the last sizeable town before the Karnatakan border, presides over a stretch of coast with a choice of vast, palm-fringed beaches of golden sand, few of which ever see more than a handful of visitors. And there’s some delightful, low-key accommodation there too, my preferred option being the lovely Kannur Beach House.

Hosts Nazir and Rosie (descendants of local Muslim aristocracy who dropped out of the IT rate race in Singapore) are authorities on Theyyem – a form of ritual theatre which takes places in the surrounding villages over the winter months. Theyyems don elaborate masks and costumes before entering trances in which they leap, dance and wave blazing torches in rituals that typically last all night.

Further north still, the Neeleshwar Hermitage is the nicest resort if you’re looking for a touch of understated luxury in an idyllic setting. The location, beside a heavenly beach, couldn’t be better, and the accommodation is in beautiful, Keralan-style chalets with palm-thatch roofs and shady sitouts. There’s a huge pool and top-class Ayurveda spa, and in the evening, a programme of lectures is offered on different aspects of south Indian culture, be it temple architecture or Theyyem.

The Last Boatyard

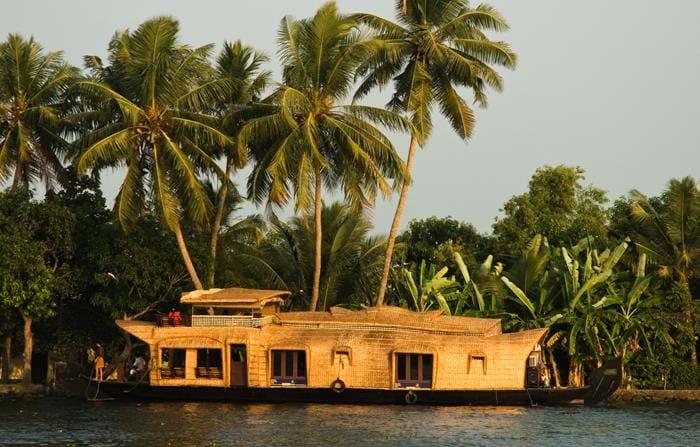

A memorable discovery during my last visit to Kannur was a boatyard, half an hour’s drive north of town, where large, ocean-going ships are still made entirely of teak – the last place in Kerala these ancient skills survive. No written plans and very few power tools are used in the process, knowledge of which is handed down father-to-son. The present owner is the 15th generation of his family to run the yard and was rather astonished to welcome a foreign visitor. He took me on an unforgettable guided tour, clambering around rickety bamboo ladders and scaffolding to see the khalsis, as the shipwrights are known, at work on a huge dhow.

In the past, such ships would have been used to transport spices and pilgrims across the Arabian Sea. Now they’re commissioned by wealthy Gulf Arabs as pleasure vessels or floating casinos.

Fishy Business

At the opposite end of the state, in the far south not far from the capital Trivandrum lies Vizhinjam, a major fishing harbour for thousands of years and a great place to visit in the early morning if you happen to find yourself within range. Keralan fishermen and their wives love to don day-glow colours, and paint their boats in a similarly striking fashion – all of which makes for some fine photo opportunities.

I spent a compelling couple of hours just after sunrise one cloudy morning, as people were landing baskets of glistening pomfret and shark, mending their nets and relaxing after a hard night’s work.

Everyone was delighted to have their photo taken, even the women, and I managed to capture some atmospheric portraits.

What these images barely hint at, of course, is the pungent and pervasive aroma of rotting fish!