Myanmar 15.04.2020 Updated: David Abrams

Thanks in part to its geography, Myanmar has some of the most unique traditions and ranks among the most culturally distinctive countries in Asia – one of those places you travel in where every day brings novelty and fascination. For those yet to discover Southeast Asia’s quirkiest and most unique nation, we’ve picked out some of its more weird and wonderful traditions and cultural traits.

Thanaka

Perhaps best associated with Myanmar, this unique tradition can be seen almost from the moment you step off the plane. Walk down any street in Myanmar and you’ll notice that most of the women and children you pass will have pale yellow paste smeared over their faces. Ranging from streaks along the cheek bones to full face packs extending from chin to forehead, the masks are made of ‘thanaka’ powder, derived from the bark of a medicinal tree that grows in the hill country. Burmese people believe it improves the complexion, protects skin from the effects of the sun, prevents wrinkles, is generally a cure-all – and of course is flattering! What do you think?

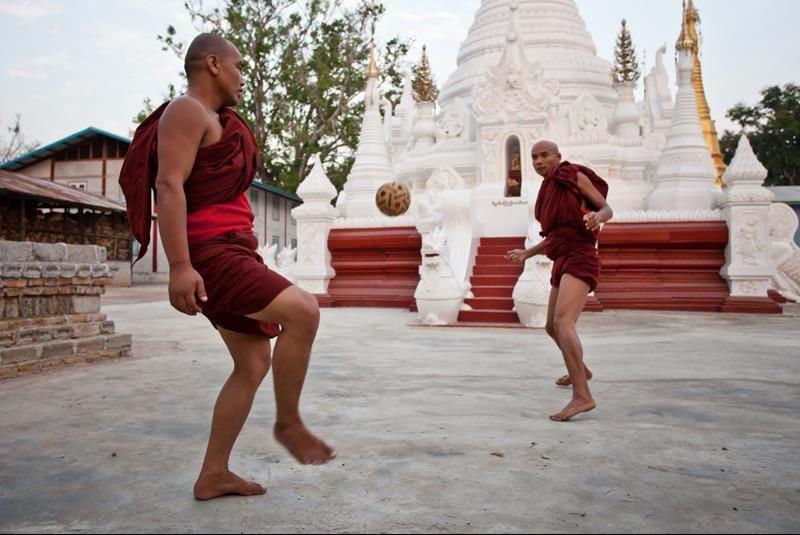

Chinlone

Myanmar’s national game is a form of ‘keepy uppy’, in which participants pass a woven cane ball to each other without touching it with their hands or allowing it to hit the ground. Apart from notching up the maximum number of passes, the object is to pull off the fanciest moves, graded according to their degree of difficulty. It’s a cooperative rather a competitive sport, but tournaments are held throughout the winter months in special sand-floored ‘chinlone’ gyms. Accompanied by traditional Burmese orchestras and a rapid-fire commentary, these matches generate huge excitement and occasionally make national headlines. You’ll see why when you watch this video here, which also demonstrates why the game is as much an art form as a sport.

Nat Worship

As well as Buddhism, most people in Myanmar adhere to a traditional, uniquely Burmese religion based around the worship of nature spirits, or ‘Nats’. Representing human flaws or vices, there are 36 Nats in the officially sanctioned pantheon, for which you’ll find shrines in most large Buddhist temples. They’re the focus of rather raucous festivals.

The Leg Rowers of Inle

Cradled by the Shah Hills, Inle Lake forms the focal point of a region inhabited by several ethnic minorities, among them the Inthe, who live in stilt houses around the lakeshore. Fishing is their traditional occupation, undertaken in flat-bottomed canoes propelled using a rather odd rowing technique: the paddle is manoeuvred by the foot, while the fisherman stands on one leg atop the tailboard. One of the great pleasures of visiting the lake is a sunset cruise, when you’re treated to the spectacle of dozens of local leg rowers laying their nets as dusk, as the water swirls with magenta and tangerine reflections.

Lotus Silk

As far as we know, Inle Lake is the only place in the world where silk is woven from the stem of the lotus plant. This centuries-old craft these days supplies visitors with vibrant and wonderfully exotic souvenirs, hand-woven in stilted, teak-built workshops by local Inthe women.

Shan Stupas

A symbol of Buddhist ‘dharma’ for two-and-half thousand years, the stupa is ubiquitous in Myanmar, where it called a ‘paya’. The largest and most illustrious, of course, is the resplendently gilded Shwedagon Paya in Yangon, but in the wilds of the Shan Platea, the Pa-o minority have invented their own, rather slender version, built using brick and ornate stucco decoration, topped with brass finials.

Teak Palaces

Once forming vast forests in the region’s foothills, teak has long been the building material of choice for the Burmese, thanks largely to its durability – the wood is extraordinarily resistant both to the effects of the monsoons and the destructive attention of termites and other insects. Numerous teak monasteries survive across the country, but only one of the great wooden palaces that adorned the former Konbaung capital of Mandalay survived the fire storms of World War II: the Shwenandaw, which (thankfully for us) King Thibaw removed from the main royal enclave in the 19th century.