India 31.03.2024 John Gimlette

Living it up on the Roof of the World

by: JOHN GIMLETTE and family discover the beauty of altitude in India’s highest and most northerly region, Ladakh.

Life at extreme altitude can be wild and fun. Sure, the air’s thin; in winter, most rivers freeze solid. But, in Ladakh, everything goes a little crazy during its tiny summer, from May to August. The colours deepen, the wildflowers erupt, the rivers boil, and everyone’s out, looking by turns medieval and happy.

We spent a fortnight in ‘Moonland’, as people call it. It seldom rains, and the mountains rise to about twice the height of the Alps, at nearly 8,000m. This makes it one of the barest, emptiest, and most beautiful places on Earth.

Although this is India, Ladakh often feels more like Narnia. There are no rice padis or railways, and – thanks to politics – the entire region was sealed off until 1974. Ladakh had been the Lost Kingdom.

Meanwhile, its people, the Ladakhis, survive on glacial meltwater, and grow their barley and apples in long green ribbons along the riverbanks. Often, they wear heavy black robes, and are handy with slingshots. This is no place to be a wolf.

We began our trip in the capital, Leh. An ancient way of life is still in full swing. The national sport is archery, and the old town is built of mud bricks and willow. There are no traffic lights, and the main car park is double the size of a polo field. Astrology is big business, and, like everyone else, we went to see a clairvoyant. Everything will be fine, she said, whatever we asked.

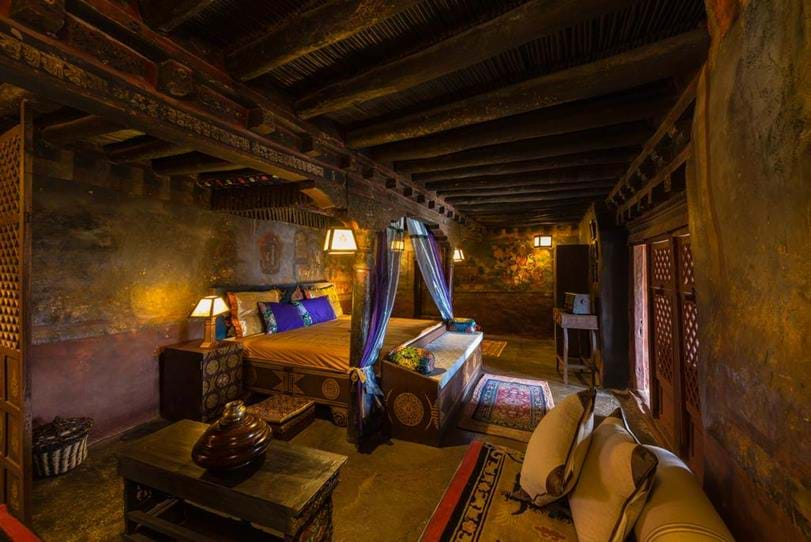

Transindus even arranged for us to have tea with the king, Raja Jigmed Wangchuk Namgyal, who’s now a hotelier. His family lost power in 1834, when the Dogras invaded. He didn’t seem to mind. The rooms at Stok Palace, his hotel, were surprisingly cosy, like the inside of a Tudor warship.

There was lots to do for a family like ours. We did a short course on Ladakhi cuisine, which is all about barley, apricots and ingenuity (@artisanalalchemy). We also learnt how to dye Pashmina wool and to weave our own two-inch scarves. Only a third of the raw wool is usable, and costs £150 a kilo.

We stayed in two hotels on our visits to Leh. The first, Saboo Resort, was out in the hills, overlooking the Indus. It was cool and funky and a favourite with Bollywood stars. Everywhere there were movie posters, and the sweet peas were planted in old ammunition boxes, marked ‘TNT’.

The other hotel, The Grand Dragon was more central and palatial, a visual feast of lacquer and dragons. All this Tibetan décor was obviously popular with the Dalai Lama’s men. One night, a huge delegation of monks and abbots gathered in the gardens, to enjoy roasted barley and salted tea.

From Leh, we set out to explore three great valleys. For this, we had a guide called Dorje. Like all the Ladakhis we met, he was a devout Buddhist, affable, kind and tough. His parents had been farmers out in the mountains. ‘When I was four,’ he once told us, ‘I left home to go to school. It was a four-day trek to the nearest town.’

Although twice the size of Belgium, Ladakh has few roads. Some are closed for months on end or get swept away if ever there’s a ‘cloudburst’. Others zig-zag upwards through the gorges or skirt some great abyss. Keeping it all running are huge workgangs, often women dressed in colourful saris.

One road we took, over the Khardung Pass, runs past the ‘Highest Café in the World’. For many Indian tourists, this is their first experience of snow, and they scoop it up in disbelief. Once, the Silk Route came this way, funnelling goods from China to Europe. Up there, at 5,359m, you’re almost flying.

Monasteries were a prominent feature of these mini-adventures. They always appeared in the most improbable places, embedded in mountain walls (like Ensa) or perched twelve storeys high on the summit (like Thiksey). In some, like Lamayuru, the frescoes were still fresh and fearsome even though they were 1,000 years old. Alchi, meanwhile, is ‘the Sistine Chapel’ of the Himalayas.

Although I was a useless student of what it all meant, I loved these places. Once, we attended early morning prayers. It’s a beautiful if mysterious event, involving chanting and drums and enormous kettles of buttery tea. Although the lamas, or monks, would pray twice a day for four hours each, some were only small boys. ‘My brother’s a monk,’ said Dorje proudly, ‘He joined aged six.’

Although I was a useless student of what it all meant, I loved these places. Once, we attended early morning prayers. It’s a beautiful if mysterious event, involving chanting and drums and enormous kettles of buttery tea. Although the lamas, or monks, would pray twice a day for four hours each, some were only small boys. ‘My brother’s a monk,’ said Dorje proudly, ‘He joined aged six.’

Our first great valley, the Indus, has long been a cut-through for traders and hunters. Domkhar’s petroglyphs, depicting ferocious wild sheep, are at least 2,000 years old. Villages like Tia now feel Hobbity and ancient with their secret courtyards and tunnels. It reminded me of Tuscany (except ten times as high).

We stayed at The Apricot Tree, at Nurla. The owner’s grandfather had started out running mail for the British. Things had prospered and now the family had a handsome, cloistered hotel dangling over the river. Life however still revolved around apricots: ornamental, medicinal and lunch.

The other two valleys, the Nubra and the Shayok, were even more magnificent. In this gigantic u-shaped landscape, towns and villages shrink to nothing. Meanwhile, huge sand dunes collect by the rivers, and this is where the camels live. For £3.50, these survivors of ancient trade can now be hired, and you can run your own little Silk Route across the valley.

Even now, this is a strategic hotspot. Upstream of the Nubra is the Siachen Glacier, and, beyond that, Pakistan. India and its neighbour still contest the glacier, and occasionally slug it out at 5,400m. That explains all the roads and the convoys. Once, we even saw an army haytruck, heading north with fodder for the mules.

Defiance defines these valleys. Despite the cold, the heat, the politics and the landslides, life is lived to the full. Hydroponic farming is the new craze and whatever’s left of the barley goes into beer. Out in the sand, the locals have set up a zip-line and go-kart track, and, at the point of Pakistan’s furthest advance (in 1999), there’s a gigantic golden Buddha.

Best of all was ‘The House of Trees’ or Lchang Nang. A few years ago, this little corner of high altitude desert was transformed into a very chic mudbrick hotel. For our teenager, Lucy, it was heaven; the cottages; the firepit; the gorgeous buffet; the cat (‘Biscuit’) and the little outdoor cinema they set up in her garden.

Our last few days, we went trekking. We camped near Rumbak, high in the Hemis National Park. This is snow leopard country, and, although we didn’t see any, we did see their dinner: a herd of blue sheep skittering around up in the cliffs.

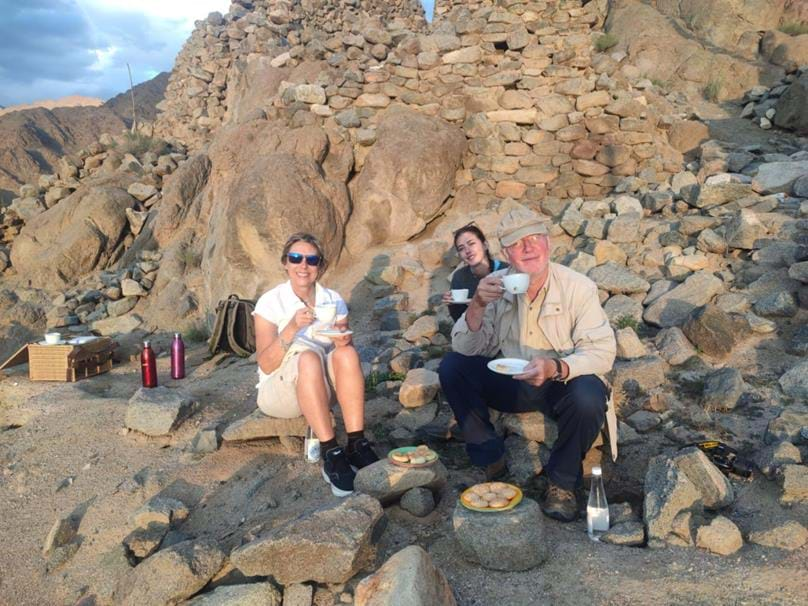

Our best trek was up a pass called Stok-la, a round trip of about 10 miles. At first, there were shrines and stupas, then yaks, and then nothing but the desert. Eventually, however, we reached the top (4,820m) and there was our entire fortnight, spread out below. I love that idea: Ladakh once almost disappeared, and now you see it in all its glory, all at once.

Biography: John Gimlette

A barrister by profession, John's love of travel sees him flourish as an award-winning author of five books: At the Tomb of the Inflatable Pig, Theatre of Fish, Panther Soup, Wild Coast and Elephant Complex. In 1997, he won the Shiva Naipaul Prize for travel writing, and his first two books were nominated by The New York Times as being among the '100 Notable Books of the Year'.

In 2012, Wild Coast won the Dolman Travel Book Prize for 2012 and was later named by The Daily Telegraph as one of the 'Twenty Best Travel Books of all Time'. John's travels have taken him to places as diverse as Eritrea and Laos, through most of South America, and to over eighty countries in between'.