India 14.03.2024 Updated: David Abram

Travel writer David Abram on why India’s little visited top right-hand corner is perfect for anyone seeking a taste of old India

I’m reclined on a day bed made of Burmese teak in the grounds of a rather splendid, 250-year-old mansion, a stone’s throw from the banks of the Hooghly River in West Bengal. All around me, the chatter of birds and rustling of leaves drifts from the surrounding screen of coconut palms and acacia trees, along with occasional moan of a water buffalo languishing in the rice paddy nearby.

A pot of Darjeeling tea at my side reminds me of the remarkable vista of Himalayan snow peaks I was gazing at this time yesterday, seated on my hotel balcony high in the foothills. From my present position, amid the tropical heat and vegetation of the Sunderbans, such a vision feels like an improbable dream.

Over the past twenty days I’ve experienced a parade of extraordinary spectacles, from sunrise on the world’s second-highest mountain to a one-horned rhino calf caked in mud. I’ve seen dancing monks, multi-coloured Tibetan monasteries and bridges made from living trees. I’ve also visited Kolkata (Calcutta) for the first time – realizing a life-long ambition.

My whistlestop tour of the northeast will not, I hope, be my last visit to the region. I’m already planning another one soon. In the meantime, here’s a roundup of my personal highlights from the trip, beginning with one of the most atmospheric hotels I’ve ever stayed in.

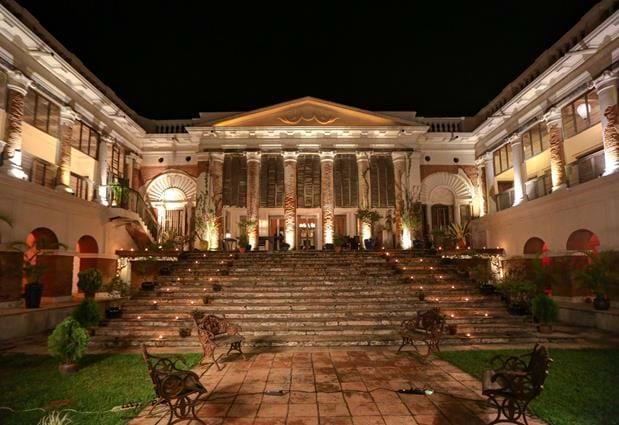

Fit For A Nawab

Located amid the flat, riverine landscape along the Hooghly River, Rajbari Bawali palace once belonged to a clan who rose to prominence by quashing a rebellion on behalf of the Mughals. Once the family’s fortunes had waned, it lay empty and snake-infested, with trees growing through the walls, until businessman Ajay Rawla stumbled upon it. Three years of painstaking work ensued, restoring the Neo-classical pile to its former glory. Filled with period furniture and art, the building now offers a unique heritage experience, evoking the European-influenced opulence of mid-18th century Bengal. Village walks, cookery demonstrations and visits to local Krishna temples are on offer if you tire of lazing and gazing, which I didn’t.

Living Bridges

The Khasi Hills of Meghalaya boast the highest rainfall of anywhere on earth (12m/year, to be precise – 20 times greater than London!). It can rain here at any time, and downpours often continue for weeks on end. It is, however, worth braving the deluges to see the so-called ‘Living Bridges’ of Cherrapunjee. By training roots of ficus trees over rivers, the predominantly Christian inhabitants of Cherrapunjee village are able to traverse troublesome mountain streams when they are in spate. The bridges take more than a generation to make. We were lucky enough to see one family doing a bit of maintenance work, twining ficus fronds around thicker branches and fastening them with wire.

Hornbill Festival

In British times, the Naga tribesmen had a fearsome reputation as ‘head hunters’. A century of missionary activity, and incorporation into the Indian republic, has seen an end to the blood-thirsty practise, but the Nagas have retained many of their traditional ways. The best place to experience them is the annual ‘Hornbill Festival’, a vibrant celebration of Naga culture staged near the state capital, Kohima, in early December each year. In addition to performances of songs and dances, the event features displays of Naga crafts, sports, herbal medicine, archery and wrestling. We stayed at a luxury camp, deep in the forest near the showground, for three nights, alternating trips to Hornbill with visits to local villages. The whole experience was unforgettable. Far from the formidable characters one might have expected, the Naga people we met were welcoming and delighted to be the subject of so much attention!

Beast of the Brahmaputra

My visit to the world-famous Kaziranga National Park, on the banks of the Brahmaputra in Assam, ticked off two firsts for me. One: I finally got to ride an elephant. And two, I saw a one-horned rhinoceros – both at the same time! I’d never sighted a rhino in the wild before, which isn’t surprising as there are perilously few of them left, and those that do survive nearly all live here, or in similar terrain in parks in Nepal. We were really lucky to see a calf with its mother on our third and final morning – a sight that inspired some optimism for the future of this magnificent animal.

River Cruises

Travel in northeast India doesn’t necessarily have to mean “trains, planes and automobiles”. The region’s rivers were for thousands of the years the principal transport arteries of the subcontinent and recently the Assam–Bengal Navigation Company commissioned three retro-style steamers to ply these ancient waterways. The cruises along the Hooghly, Brahmaputra and Ganges pause at historic sights and cultural centres, yielding a unique perspective on this little visited corner of the country. I did a short taster stretch north of Kolkata but would have loved to have continued for the full trip.

A Forgotten Palace

Central Bengal holds the remains of several pre-colonial cities whose names have been all but forgotten. Grandest of them all is Murshidabad, capital of Murshid Quli Khan, the First Nawab of Bengal. Numerous mosques, tombs and gardens survive on the site, but its crowning glory is the vast, Georgian-style Hazarduari Palace, whose great façade rises in spectacular fashion from the banks of the Bhagirathi River, a tributary of the Hooghly. Inside, a museum holds an array of sumptuous antiques from the 18th and 19th centuries. An interesting detour took us to the workshop of an artisan who carved delicate art objects from a substance resembling styrofoam extracted from a local wetland plant. Known as ‘pith’, the porous core of the plant was used to strengthen British army helmets, whence the term ‘pith helmet’.

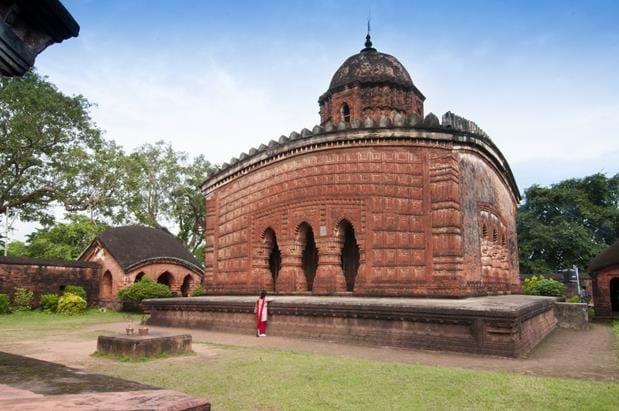

The Terracotta Temples of Bishnupur

Some of the most beautiful and richly embellished temples in India are to be found half a day’s drive north of Kolkata at Bishnupur, former capital of the Malla Rajas. Made of laterite stone and brick faced with finely carved terracotta, the temples take their cue from the form of simple Bengali village huts, whence their gracefully arched chala roofs. Tiles around the bases of the shrine depict scenes from the Hindu epic, as well as intricate floral motifs. It was a surprise to come across a collection of splendours such as this in a region that’s now such a forgotten backwater.

Glenburn Estate, Darjeeling

Glenburn is the loveliest place to stay in the Himalayan tea gardens enfolding Darjeeling. Established in 1859 by a family of entrepreneurial Scottish planters, the estate sits on a hill above a bend in the River Rangeet, its green-roofed bungalows surveying a vista of ethereal beauty. Lying in your teak four-poster, with the French windows wide open and a tray of bed tea at the ready, you can literally gaze across the treetops at the distant snow-clad summit of Kanchenjunga. The light, airy suites, which open on to flower-filled verandahs, are all effortlessly refined, from their toile de Jouy upholstery to white-painted wicker chairs.

Paradise at the Road’s End

One of the most memorable road journeys I’ve ever done in India was the haul through the foothills of the Himalayas in Arunachal Pradesh to Tawang Monastery. It followed the course of a fragile, unfinished military road that climbs from Bhalukpong, on the Assamese border, through miles of misty mountains and isolated fortress towns to the 4,300-metre Sela Pass. Beyond, amid an amphitheatre of high, snow-streaked mountains lay the tantalizingly remote Buddhist monastery of Galden Namgey Lhatse. The complex houses 500 monks and is one of the largest of its kind in Asia.

Sunrise at Pelling

I’m not generally one for an early start, unless there’s a copious amount of Italian coffee involved. But for some spectacles I will forgo a pre-prandial caffeine fix, and none could possibly be more worth the sacrifice that the sight of the day’s first rays illuminating the ice fields of Kanchenjunga, the world’s second highest mountain. I didn’t have to walk far in the darkness to reach the viewpoint. The great massif was actually visible from my hotel balcony at Pelling, in the Himalayan state of Sikkim. So by the time I’d attached my camera to my tripod, a smiling waiter in a woolly hat had appeared with a pot of Darjeeling tea, which I used to warm my hands. Five minutes later, the serrated summits of great massif on the northern horizon suddenly glowed crimson, as if someone had flicked a switch. I was so enraptured I almost forgot to click the shutter before the shadow line eased down the flanks of the mountain, and the ice fields turned a gleaming, ethereal white.

For more information any of the locations described above, and how they might be tied into a tailor-made itinerary, contact one of our specialist consultants on