India 27.03.2017 Updated: David Abram

I’ll never forget the one and only time I’ve ever ridden on the roof of a bus. I was a 21-year-old student, travelling on a shoestring around Kashmir and Ladakh, in India’s northwest Himalaya. The bus in question was crammed to bursting point with Buddhist pilgrims making their way from the region’s capital, Leh, to a monastery festival higher up the Indus Valley, in the village of Hemis. I’d figured the only way I was going to get to experience the stupendous mountain scenery along the route was to join the other lads of my age up on the “observation deck”.

Suffice to say, the views were more than worth the risk (or so it seemed to me at the time – I’m not sure I’d feel the same way now I’ve got a couple of adventurous kids of my own!). But what I wasn’t expecting was that the vast ice peaks and scree slopes could possibly be upstaged by the festival.

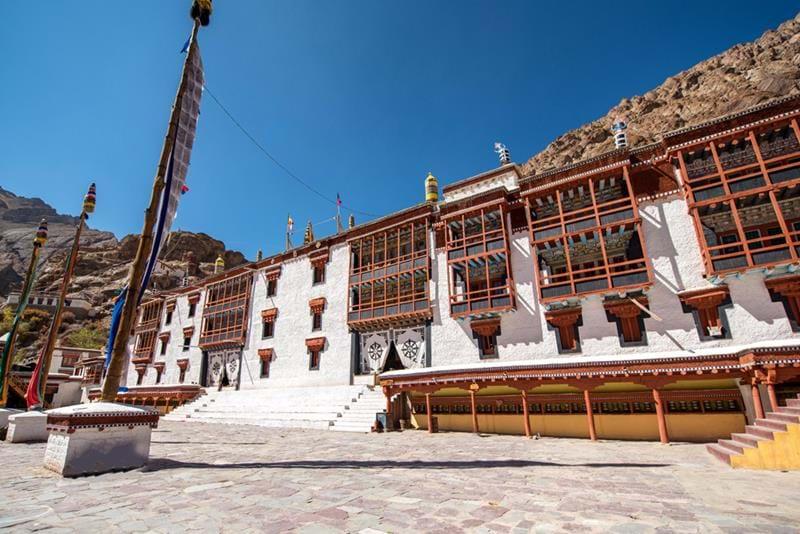

Hemis nestles inside a fold in the colossal wall of mountains sweeping from the left bank of the Indus River. Overlooking a swirl of barely terraces and little cuboid farmsteads festooned with prayer flags, it’s a textbook Tibetan monastery – home to over a hundred monks and novices who each year host the region’s largest and most exuberant religious gathering.

The focal point of the event is a display of masked ‘cham’ dances, for which the monks parade in fabulous, polychrome costumes capped with oversized masks and brimmed hats draped with yellow, blue, red and white silk ribbons. Accompanied by an orchestra of Tibetan trumpets and percussion, they skip and spin in synchronized circles around a central ceremonial flagpole, watched by thousands of sun-kissed Ladakhi faces, and a fair number of rapt foreigners.

Hemis used to be one of the only monasteries in the region that held its annual festival in the summer (most of the others staged theirs in the depths of the winter when there was no farm work to disrupt). Nowadays, though, to capitalize on the tourist dollar, the majority have switched to the warm, dry and sunny period between June and September, when the high passes giving access to the region are free of snow and the flow of visitors dependable.

The last Hemis Festival I attended, in July 2013, was a special one because it featured a rare unfurling of what is reputedly the world’s largest thangka – a giant Buddhist icon painted on applique panels of brocaded silk. It depicts the hero of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism, Padmasambhava (aka ‘Guru Rincpoche’) and is held in great veneration by Ladakhis, who believe that a mere glimpse of the mighty image is enough to ensure health and good luck for the twelve years until it is next unveiled.

For travellers, Hemis offers a perfect way to experience authentic Ladakhi culture at its most vibrant and otherworldly. As well as the extravagant costumes, music and dance of the cham rituals, there’s the traditional dress worn by local festival goers to admire. Most married Ladakhi women take the opportunity to wear their finest peraks – large headdresses encrusted with chunks of coral, turquoise and tiger’s eyes – in addition to their heaviest silver jewellery and brightest silk cummerbunds, wrapped around ankle-length, home-spun robes. The men also ditch their regular puffer jackets and ball caps in favour of traditional attire, making for some marvellous photo opportunities.

The journey from Hemis back to Leh in July 2013 was a rather more comfortable and safe one than my rooftop adventure of 1986! Strapped into a sleek TransIndus Landcruiser we sped over roads that were far less weathered and pot-holed than the lane I live on in Somerset. And the accommodation was a big improvement too: a luxury tent camp at the foot of spectacular Thiksey monastery, with a glorious view of the monks cottages spilling down the hillside below the prayer halls, and of the plumes of clouds and spindrift trailing from the summit of Stok Kangri on the far side of the Indus – surely one of the finest views in the Himalayas.

NEED TO KNOW

When does the Hemis Festival take place?

The precise dates of the event are pinned to the Buddhist lunar calendar, but it usually falls in early July. The cham dances run for two days.

Is it difficult to find accommodation?

Over the festival period, rooms in and around Leh may be in short supply so it’s always wise to book ahead as far ahead as possible. Contact one of our Ladakh specialists to discuss the options.

How, after travelling all that way, can we be sure of getting a seat with a good view of the dances at the festival?

True enough, the best places tend to get nabbed very quickly. But your TransIndus guide will be a local who knows the event and monastery well, and will be able to secure you a suitable vantage point, as well as talk you through the meanings of the dances.

How long would I need to be away?

With many flights connecting Delhi and Leh in the summer months, you could feasibly travel to Ladakh, see the festival and leave within as little as one week. However, the region deserves longer and slots together nicely with two- and three-week itineraries covering the Kullu Valley and neighbouring Kashmir.

What else is there to see and do in Ladakh?

More than a dozen monasteries overlook the floor of the Indus Valley around Leh. They’re all different, contain fabulous antiques and artworks and are set amid truly breath-taking scenery. The oldest, at Alchi, is over a thousand years old and holds a UNESCO-listed collection of murals.

There are also numerous traditional Ladakhi villages hidden up side valleys, and some of the most spectacular high-altitude lakes in the world lie within range of a day trip. With a little more time you can cross the world’s second-highest motorable road into the Nubra Valley, in the lap of the Kun Lun range dividing Ladakh from the Chinese province of Xinjiang – a spur of the old silk route – where twin-humped Bactrian camels are still used to transport crops.